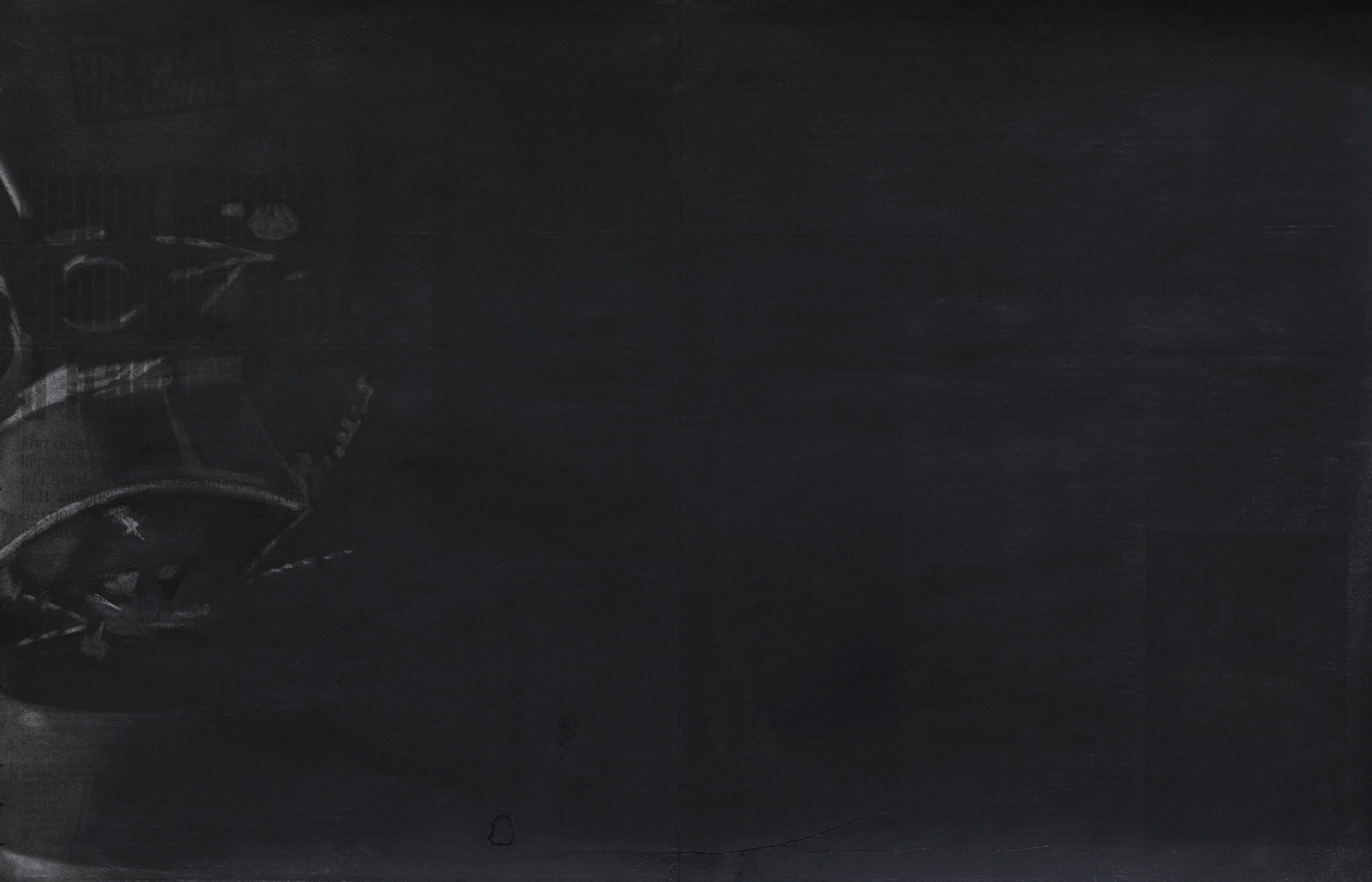

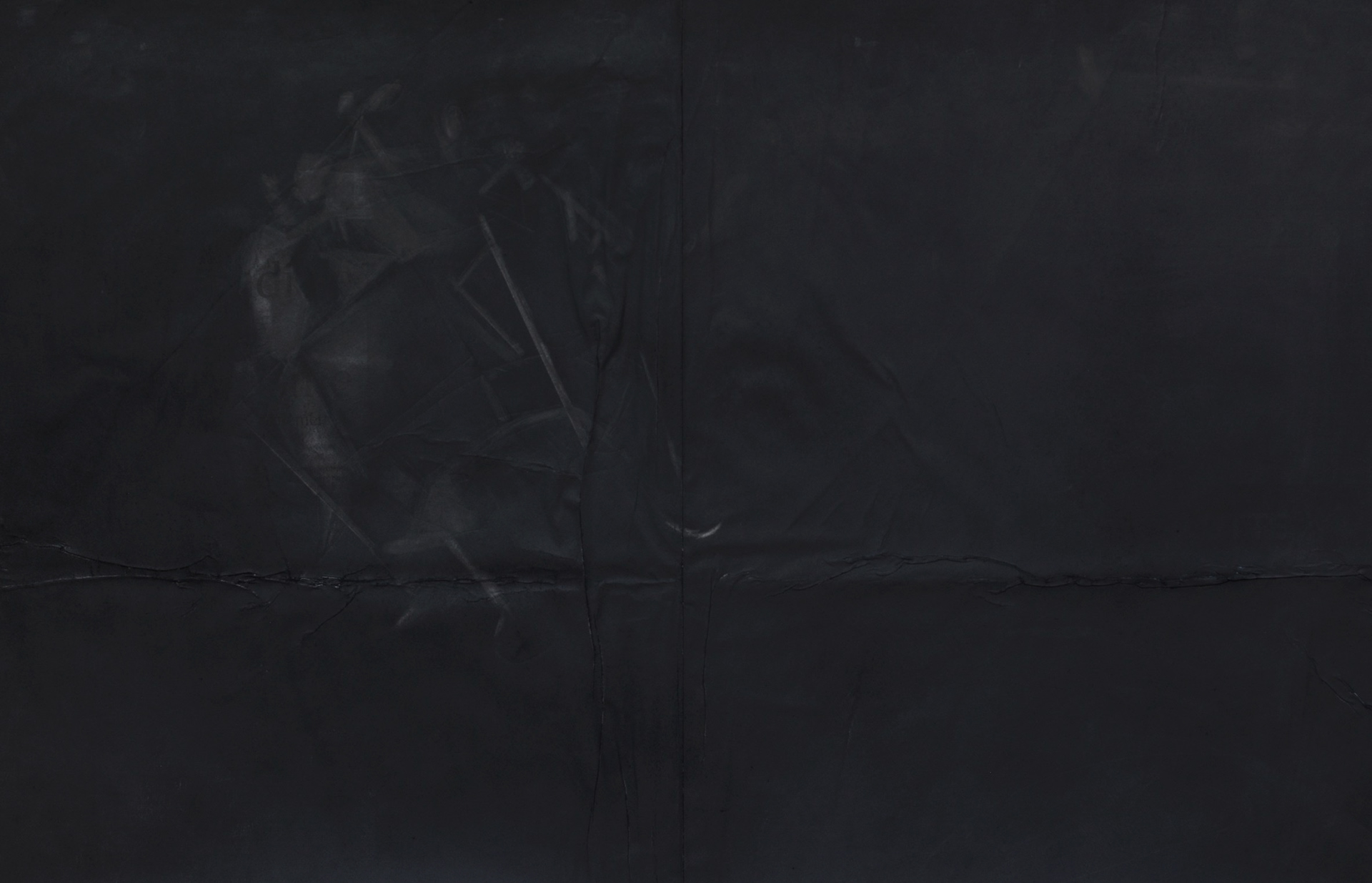

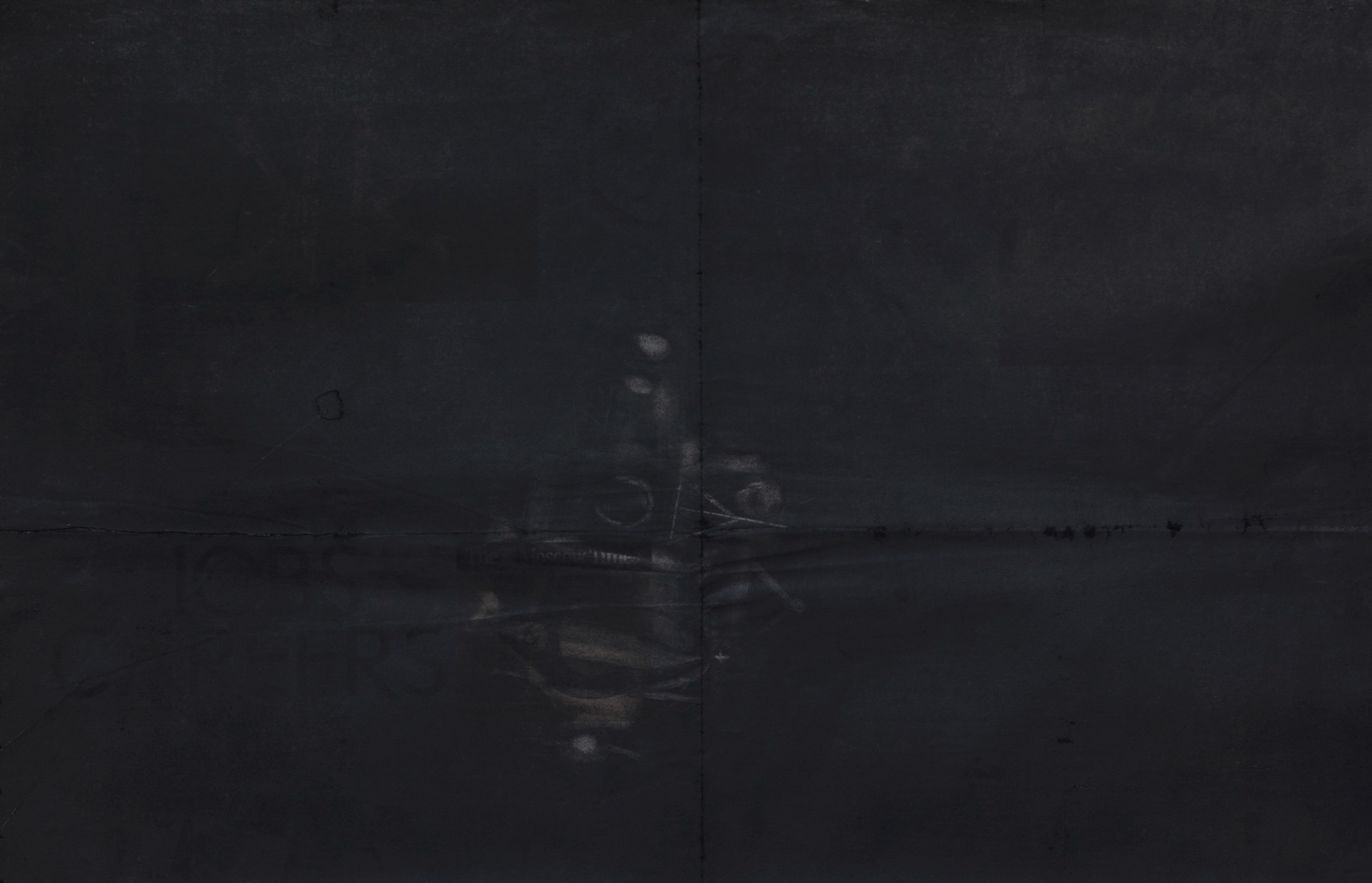

The Smell in the Air After a Firecracker Has Gone Off (2019), From the series "I remember" Charcoal on newspaper, 58 x 38 cm, Series of 31.

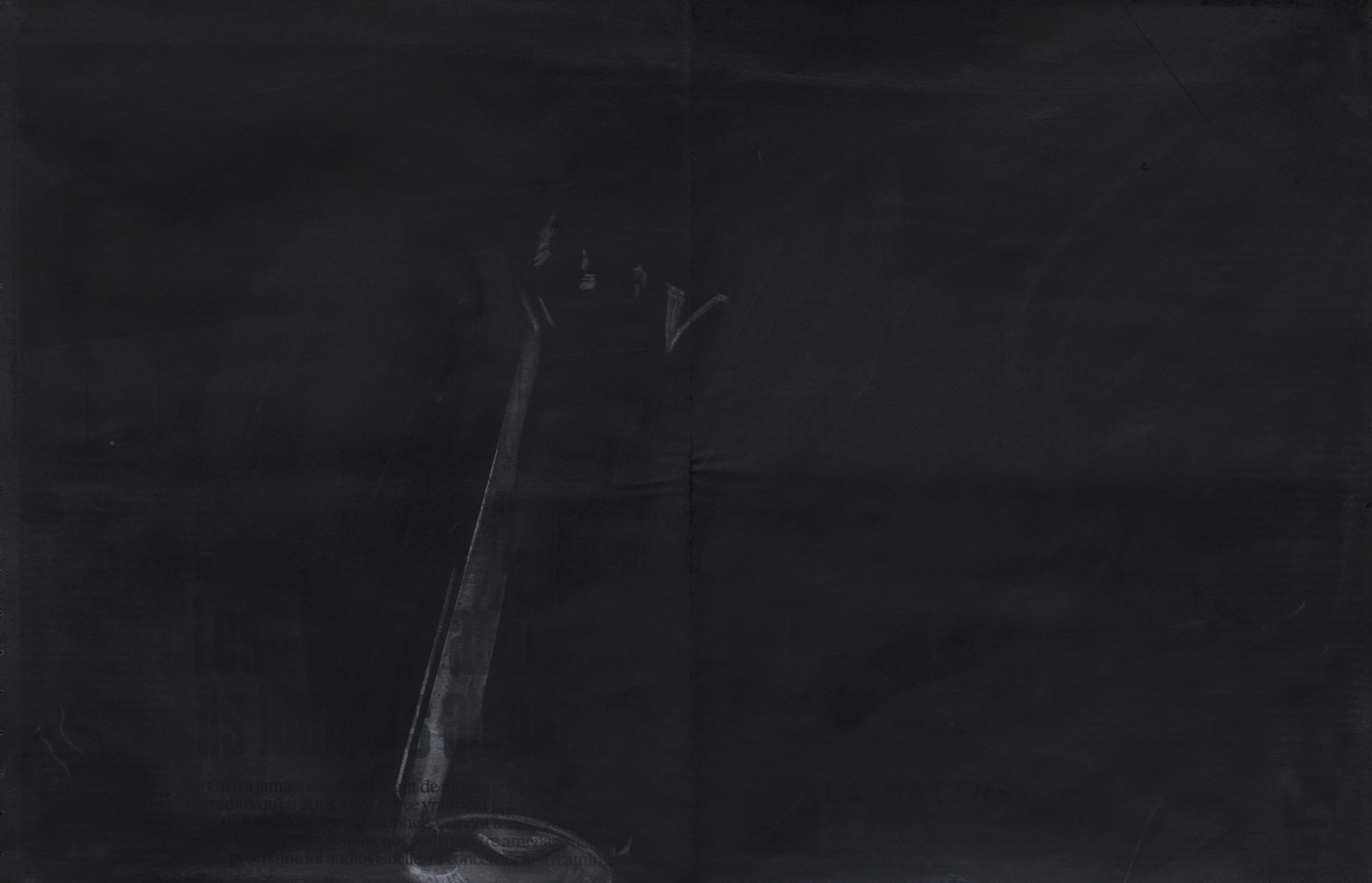

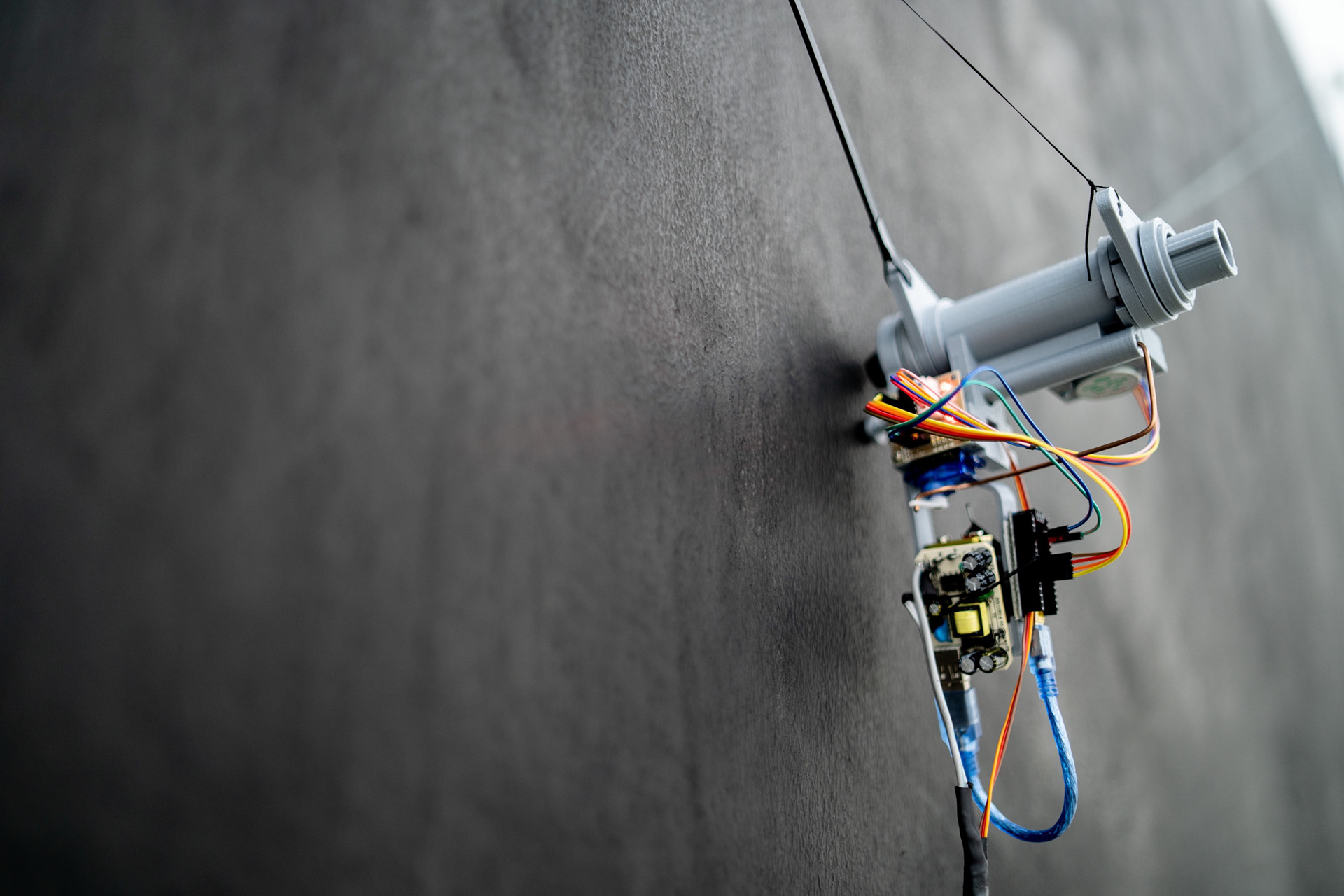

The Smell in the Air After a Firecracker Has Gone Off (2019) From the series "Trajectory" Charcoal drawing, automated machine Dimensions variable

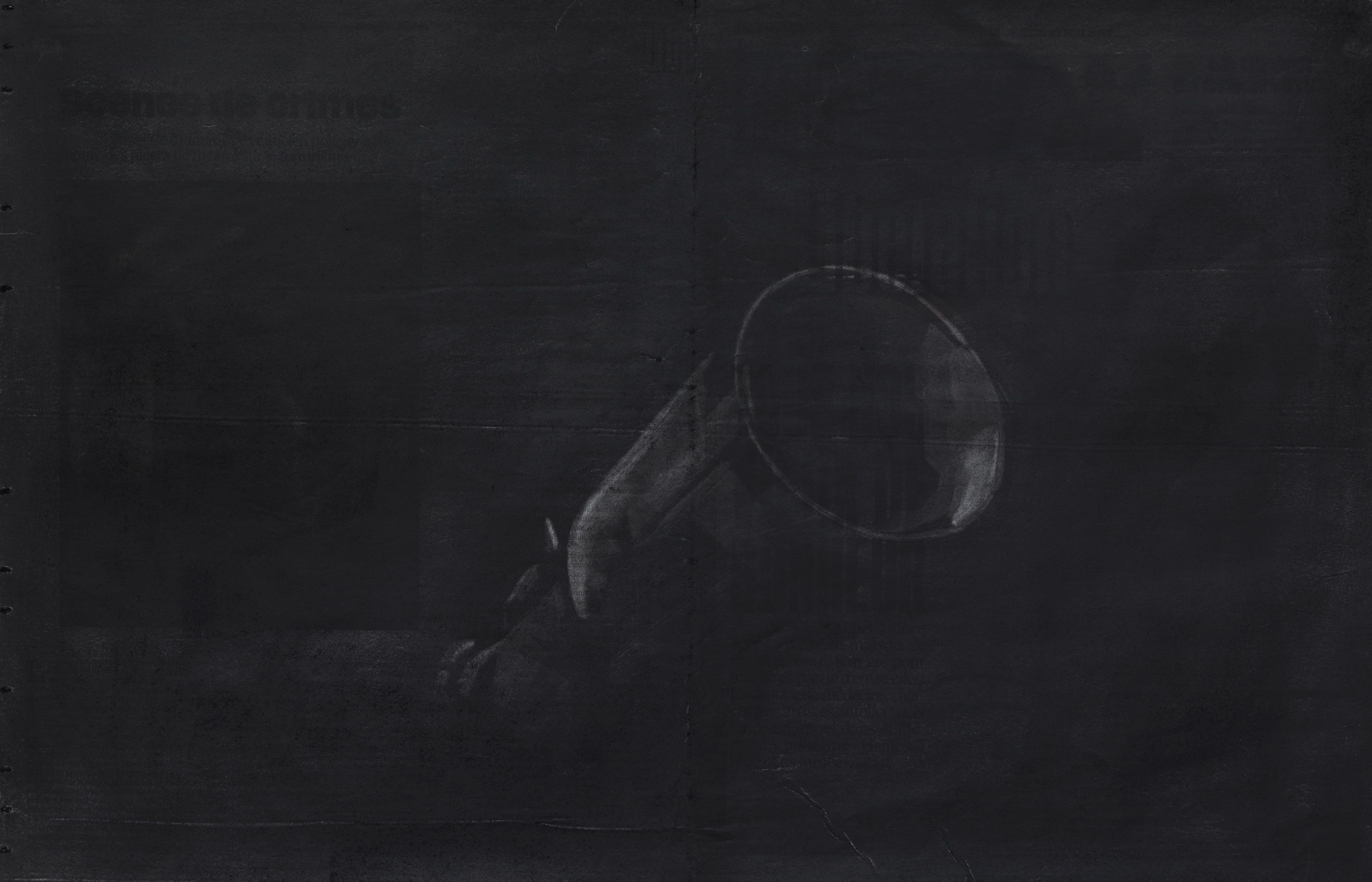

The Smell in the Air After a Firecracker Has Gone Off (2019) From the series "Just Imagine" Ceramic sculptures Series of 3

Pattara’s artistic practice takes various forms, combining photography, sculpture, drawing, and installation. This range of disciplines allows him to express time in diverse ways, illustrating how the past inhabits the present. He explores the relationship between photography and objects, images, or technology from the past. By recovering stories, neglected spaces, or forgotten images, he highlights appearances and disappearances through the passage of time, while sublimating them.

The exhibition includes ceramic sculptures (replicas of the famous cameras from the Apollo XI mission) and drawings (spacecraft, rocket launch dust), as well as an ingenious drawing machine activated for a specific duration, embodying the rhythm of time and its overlaps. Like astronomy, photography shares an interest in light and what lies beyond our perception. For Pattara, photography becomes a starting point that allows for a transposition toward other mediums. He extracts elusive fragments or specific elements from his research to pass on historical references while incarnating a form of sublime fiction and imagery.

Pattara’s works are an extension of his ongoing interest in connecting his previous photographic artworks of “forgotten spaces” and “ghost buildings” with places incarnated by spirits or those invisible to the naked eye. It is an invitation to travel beyond earthly space to the Universe, transposing objects as receptacles of the unknown—a fiction between the visible and the invisible.

Chanruechachai’s 'I Remember' is a series of drawings on newspapers that depict light reflecting on objects in the dark. The almost pitch-black images feature parts of the Apollo XI spacecraft and various other space rockets, floating on the wall against the gallery’s conventional white space, resembling space debris in our orbit. The renditions were made on newspapers that Chanruechachai has been collecting, glimpses of which remain visible. The works deal heavily with photography, image-making, and visual literacy in this post-truth era.

The artist pays close attention to the usage of materials and their meaning in all his works, having worked with newspapers as a material for more than a decade. Generally, newspapers refer to streams of information, current issues, media literacy, and biased truths. However, his use of newspapers—by superimposing photographic images onto them through digital printing or drawing—creates urgency and hints subtly at larger contemporary socio-political issues.

The shadowy, dark void is a recurring element in Chanruechachai’s works. As we step back to take in his large-scale pieces, we are drawn into this black void. The shadows are played out differently, often representing something that cannot be seen with the naked eye—unknown ghostly entities that we know exist. The work 'There is an Elephant in the Room' shows the shadow of an elephant, referencing the well-known idiom about a major problem we tend to avoid discussing despite being aware of its existence. In the exhibition 'The Smell of the Air After a Firecracker Has Gone Off…', the black void represents the emptiness of outer space. When there is no light, nothing is visible; there is no proof of either the absence or the existence of things in the dark.

Apart from the images of space debris, Chanruechachai also presents 'Just Imagine', glimpses of photographic devices that seem meant to record and capture images. Upon closer inspection, the sculptures are revealed as ceramic replicas of the cameras used in the Apollo XI mission. Ceramic is the same material used for the space shuttle shell. Standing on mirror plinths, they create an illusion of floating sculpture, and the sculpture itself becomes an illusion of truth.

Vintage technical cameras resemble weapons. While we may not be familiar with yesterday’s technology, we can still grasp the concept of a weapon. Cameras are used to record truths, but are the truths selected by the frame real? Are things outside the frame unreal? Are the cameras themselves real? And the hollowness and shadows that we cannot apprehend—are they also real? To comprehend and believe something, we need information and knowledge to fill the gaps in our minds. The disappearance of knowledge will be costly to us and our limited capacity.

'Trajectory' is a monumental drawing on one of the gallery’s walls depicting a space shuttle that, having ignited, thrusts through the sky toward the void of space. The rendition of the space shuttle on its mission is a continual performative process; more lines are added to the image by an automated machine programmed to draw black lines until the image is blackened entirely, and no information can be seen or read. The more we see something repeatedly, the more meaningless it becomes. The act of adding can also be an act of deleting, creating another meaning in the meantime: ghostly truths.

In the Information Age, we are scientifically advanced enough to know the nature of things. Today, we know that humans as a whole are becoming resistant to antibiotics. We have learned that chemicals in our brains affect our moods and vice versa. We know for a fact that vaccination reduces the risk of certain diseases, but why do people still hold ideas that contradict the facts? Chanruechachai brings up conversations about perception, truth, and belief subtly through his new works. Apollo XI was the first and only successful mission for humans to reach the moon during the Cold War. With the blurred renditions of Apollo XI shuttles and the ceramic cameras for that particular mission, the artist urges us to revisit the memories and records of Apollo XI: were they real? How do we perceive and believe such information—a fiction and a narrative in-between? The past takes us back to the present in this era of post-truth and information warfare in which we unavoidably live.

Where is this conversation going? Chanruechachai is interested in the structure of belief, information, and its re-exploration. Let us dwell on this topic for a minute: we humans have our own opinions, and we trust ourselves regarding what we believe. It is the comfort of trusting our own knowledge, as long as our memories are reliable. But when our brain is challenged by new information that contradicts existing beliefs, we tend to become skeptical. We then unconsciously begin either rejecting it or filling the gaps with theories to keep the narrative of our beliefs intact: cognitive dissonance.

The critical element here is authority. Authorities are mostly unreliable and often lack accountability, ranging from the Trump administration and dictatorships in distant lands to common administrative offices in healthy democratic countries. We psychologically reject knowledge from authorities because trust was not established. The more we doubt, the less we know. Knowledge requires a certain degree of trust in ourselves to be able to know things. Chanruechachai’s works show the gaps in between, as well as the appearance and disappearance of information, allowing us to connect narratives that reflect universal structural problems.

The ghostly case of disappearing knowledge: after a firecracker has gone off, there might be nothing left to assure us that its explosion took place, except the temporary and fragile invisible scent, which dissipates every second. When there is no longer sensory evidence of the event, is the event still real, or has it disappeared along with the smell? Can we trust our non-visual senses instead of photographic images (which can be fabricated) to know that the firecracker went off if we did not see it?

In July 1969, two people stood on the moon; the event was real. On top of that, the skepticism about its existence was just as real. The ideas about the uncertainty and disappearance of knowledge are real. The social and political structures and problems that lead us to perceive, apprehend, or reject information are also real, and they could be the root of it all. The works of Chanruechachai are indeed real. The drawings of space shuttles in dark empty spaces are real; the ceramic cameras could not be more real; the blackened drawing on the wall is also real; the authorized automated machine is real. Chanruechachai’s questions are genuine, as is the artist himself. They are all real.

Pratchaya Phinthong

12 July 2019, Bangkok